Discover how financial institutions can transform financial wellness from a cost center to a profit center. Learn strategies for implementing successful Financial Wellness Centers (FWCs).

Introduction

In an era where financial security is increasingly elusive, many banks tout 'financial literacy' as a core mission. But is it truly making a difference? The stark reality: 78% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. It's time to move beyond well-intentioned programs and create a sustainable, profitable model for financial wellness. Let's explore how banks can build Financial Wellness Centers (FWCs) that not only empower customers but also drive significant revenue.

1. The Stark Reality: Financial Wellness in Crisis

- The shift from defined benefit pensions has thrust individuals into a complex financial landscape, where many are struggling. Studies reveal alarming statistics: a majority of Americans are financially vulnerable, and retirement savings are inadequate. This isn't just a societal issue; it's an opportunity to differentiate your financial institution.

- Fourteen percent of people who feel their banks help them with financial wellness.

- Financial institutions have a responsibility to address this gap, but altruism alone is not a sustainable solution.

2. The Problem: Financial Literacy as a Cost Center

- Currently, financial wellness initiatives often operate as cost centers, driven by compliance or community relations. This approach fails to align with the core business objectives of profitability and growth.

- Anne Shutt's (Midwestern Securities) insights at a recent conference highlight the disconnect: customers aren't feeling supported by their banks' financial wellness efforts.

- The current model serves some constituencies at the expense of others.

3. The Solution: Transforming Financial Wellness into a Profit Center

- Introducing the Financial Wellness Center (FWC): A New Model for Success.

- Treat it like a branch: Dedicated personnel, clear objectives, and measurable results.

- Staff with financial coaches and support staff, not just traditional bankers.

- Integrate financial wellness into the customer onboarding process. Use the Know Your Customer process to also understand the customer's financial wellness. Offer a financial wellness opt in program.

- Implement a small quarterly fee for the FWC program. (Consider waiving initially to build momentum.)

- Bring current customers into the FWC using observable data, human judgement, and generative AI.

- Revenue Streams and Profitability:

- Account integration: Incorporate FWC client accounts into its revenue stream.

- Fee-based services: Offer credit score monitoring, bill negotiation, and other value-added services.

- Increased customer engagement: Higher engagement leads to increased account activity and profitability.

- Address the low balance issue by recognizing that this is an investment in the customers' future, and that the FWC is a place for them to grow their financial health.

- The FWC will have less overhead than a physical branch.

4. Measuring Success and Driving Growth

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs):

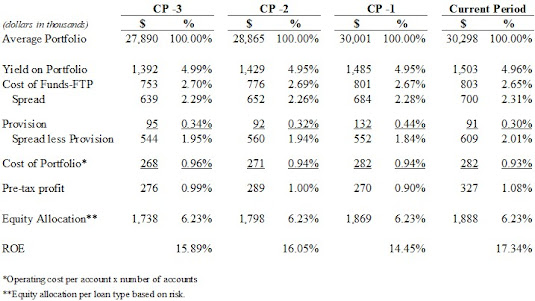

- Pre-tax profit as a percentage of average deposits (e.g., 50 basis points).

- Customer adoption of personal financial management tools.

- Improvements in customer net worth and credit scores.

- Customer graduation to wealth management services.

- When customers reach the 'Accumulating Wealth' stage of their financial life, seamlessly transition them to your wealth management division. This creates a natural pipeline for high-value clients. Don't wait for high-value clients to grace your door, build them.

5. The Benefits: A Win-Win for Banks and Customers

- Enhanced customer loyalty and retention.

- Increased profitability and revenue diversification.

- Strengthened community impact and brand reputation.

- Empowered customers with improved financial well-being.

Call to Action:

Ready to transform your bank's approach to financial wellness? I would welcome a session with your team in how to implement a successful Financial Wellness Center and drive sustainable growth. Share this article with your colleagues and industry peers to spark a vital conversation.